InFocus

Dreaming Big: the true story of an ordinary Kiwi farmer who did something amazing

iSpyHorses -- Fri, 20-Nov-2015

Hector McLoughlin Aitkenhead, or Hec to those that knew him, was born in the summer of 1933 in Parakai, New Zealand. The son of a sheep and dairy farmer and grandson of a Clydesdale breeder, Hec was instantly immersed in the rural lifestyle. Horses were a part of his life from the get-go, his youngest daughter Shona laughs. “He reckoned he learnt to ride before he could walk.” When asked if he remembers an early experience with a horse, Hec says “yes. Clear as day,” and describes the first time he rode on his own. “We were going up Fordyce Road, driving some sheep, dad and I…he was leading me along, you see; I wasn’t very old…[suddenly he said] ‘here, here, take the rope, you’re on your own,’ and I’ve sort of been riding on my own ever since.”

Hec’s first horse was a mare called Queenie, who his father Victor (Vic) bought from Pukekohe. With Queenie, Hec discovered his love of jumping. “One day,” he remembers, “I was riding along [Fordyce Road] and Dad came along with a guy in the car…they held a stockwhip between them and I jumped back and forth over [it].” As a boy, he rode his horse to Helensville Primary School each day, leaving it in the field while he attended class and then riding back home in the afternoon. He would sometimes have to leave the horses at the blacksmith and pick them up after school when they’d been shod. When he was ten, he got a job mustering stock for farmers and droving them between South Head and Helensville. He and his pony and dog were a common sight around the area.

.jpg) A young Hec, outside his childhood house in Parakai.

A young Hec, outside his childhood house in Parakai.

It was while he was in school that Hec began entering in local A&P Shows. Often people had trouble with horses refusing hurdles, so Vic “would get me onto them to make them jump,” Hec says. When he left school, he “really got into the showing circuit,” competing from Whangarei to Hamilton. Velos, a striking bay gelding, and Killarney, “a big grey mare,” were Hec’s two top competition horses. Between them he had great success in the various jumping classes: “we used to win all the time,” he reflects fondly, remembering in particular taking out the Lightweight Hunter on Velos at Kumeu. The bareback jumping classes were another area that Hec excelled in. Of all the shows back then, Pukekohe was the hardest. “Three years I went there I only got a second prize ribbon, and I used to do better than that at most shows.”

As well as jumping, Hec entered in novelty events which included flag racing, bending and dual jumping. Games like the stockman’s race had competitors “riding around the ring, knocking bottles off the ends of the jumps cracking [their] whips.” Then there was the cigarette race, where “someone stood at the other end of the ground with a lighter, you galloped down on the horse with a cigarette in your mouth, leant over and the other person lit your cigarette and you had to gallop back. The cigarette had to be lit still when you crossed the finish line,” Hec explains.

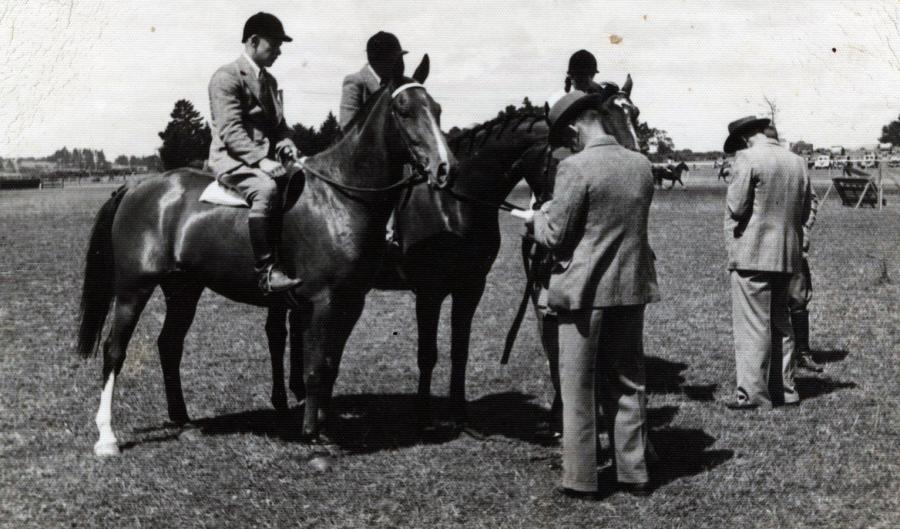

Hec competing on Velos at the Whangarei A&P Show in 1952

Hec competing on Velos at the Whangarei A&P Show in 1952

Back then, riding competitively was a different story. Safety rules were minimal, with the invention of the back protector a far-off idea. Like rider regulations, the horse world itself was more straightforward and simple – riding well was about riding well, no strings attached. You didn’t need an expensive horse or tack to be respected; you just needed to ride well. It wasn’t just the equestrian sector that was simpler, however. The whole world moved at a slower pace. Hec remembers riding along Northcote Road to where North Shore Hospital now stands. The land was originally a field in which various “hurdles” were set up, so Hec and his mate Peter, who lived nearby, would practice jumping then ride off again.

After seeing out his high school years at Whangarei Boys High, Hec returned home a young adult. He convinced the lovely Clare Bradly to go to a dance with him in the early ’50s, and married her not long after in 1955. When Vic died five years later, Hec purchased the family farm. Spanning 400 acres, the property backed onto Woodhill Forest and provided access to the nearby Muriwai Beach. The land was covered in ti-tree, rushes and lupin, and half consisted of sand dunes. Hec took the wire wove from a bed and “draped it around the front the tractor so we could drive through all the lupin and knock it over.” He then burnt the rushes and had the ti-tree cut down. To solve the latter issue, Hec planted plods of kikuyu grass and fed hay over the sand, “shaking out the seeds to grow.” To aid the growth, Hec had the farm top-dressed every year.

Hec on Velos again, this time at the Helensville A&P Show later in the ’50s.

Hec on Velos again, this time at the Helensville A&P Show later in the ’50s.

In 1970 with the farm now in a good state, Hec founded Tasman Rides, a horse trekking business which grew to become an enormous success. The idea came to him during World War II. At this time, American soldiers were stationed in Parakai to recuperate at the local mineral hot pools. Hec would ride past their camp on his way to and from school. “They’d say ‘hey, give us a ride on your horse sonny,’” he remembers, “so I’d give them a ride and they’d give me a couple of dollars.” After buying Vic’s farm, Hec was able to bring his idea to life. “Clare said ‘you’d better get it out of your system,’” so Hec settled on a name – Tasman coming from the farm’s views over the Tasman Sea – and bought six horses to get the operation going. On the first day he made seven dollars, which was “a lot for the time.” It was then that Hec realised just how profitable the business could be. “I could see us flying if it takes off,” he says. “And we did.”

With Clare manning the phones and Hec organising the horses, the company quickly took off. Business grew and grew, promoted mostly through word of mouth and regular paper ads. Hec purchased more horses to accommodate for the company’s growing popularity, eventually building it up to a herd of forty. Often he sourced horses from Bob Saunders in Papakura, but got several from “all over.” In those days there were Horse and Dog sales around the country, so Hec would head off to Dargaville, Whangarei, Pukekohe, Gisborne or Kaitaia in the truck and bring back up to six horses each time. Generally he didn’t ride the horses before buying them, instead watching how they moved and handled. Very rarely did he get it wrong. As a rule he typically avoided Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds, who tended to get fractious in the herd and didn’t hold their weight well when in regular work.

.jpg)

Hec in his competition gear at an A&P show

Like competing, safety rules around trekking were practically non-existent at this time. Clients did not have to fill out indemnity forms and there were “no helmets, no guides…nothing. [We’d] say ‘way you go…that direction,’” Hec chuckles. Many an occasion riders would return telling stories of being taken under trees by their horse, chased by magpies, or left in the dirt after their steed bolted. The one thing that remained consistent, however, was the enjoyment everyone had. The lack of rules gave trekkers a sense of freedom, and on horseback they could truly see the best of New Zealand’s landscape. Time and again, clients returned for more.

When Shona and her sister Anne were old enough Hec got them to help out too, and Tasman Rides really became a family operation. The girls would help saddle up, clean tack and occasionally ride out with people. Later Hec’s nephew Chris also joined the team, relieving him and Clare for the odd weekend. All the while the farm was being worked, providing another source of entertainment for the riders who were fascinated by the shearing, haymaking, mustering and docking. The Brownies and Guides also camped regularly on the farm to earn their various badges.

Hec leading Christine, a local blind girl whose parents thought horse riding would be good therapy, on a trek during the Sixties. Hec took Christine riding roughly once a week, and her parents believed that there was an improvement in both her balance and confidence, since confirmed by the success of organisations like Riding for the Disabled.

Hec leading Christine, a local blind girl whose parents thought horse riding would be good therapy, on a trek during the Sixties. Hec took Christine riding roughly once a week, and her parents believed that there was an improvement in both her balance and confidence, since confirmed by the success of organisations like Riding for the Disabled.

Like any company involving animals, there were characters. One of the original six horses, Mac, was an ex-trotter and refused to canter, instead ambling everywhere. Stocky, a beautiful bay, and Shona’s childhood pony Ebony were a package deal, impossible to separate. Another old mare Skippy, who the family had owned for a decade suddenly dropped foal in the middle of the yard one day. “There was no stallion on the farm and it’s a mystery how she got pregnant!” laughs Shona. Tasman Rides also had two ponies called Sparky over the years, named after each other because they looked identical. Both were tough mounts from the far North, and full of personality. Sparky II was found sheltering in the shearing shed one rainy day, and on another occasion got into the barn where grass seed was stored and ate nearly a whole bag.

Especially memorable was the paint gelding Rhino, who “kept bucking the saddle off before we could get it done up,” Hec recalls. With him and Shona on each side, they eventually got the girth tightened. After that, “he never bucked again. He was a perfect bloody horse, actually,” Shona says. Then there were the favourites, Strawberry and Heidi. Strawberry was an ex-polo pony, who came to Hec blind in one eye. Despite this, she was one of their best horses. “You could do everything on her,” he says. Heidi, on the other hand, was never meant to be a trekker. Hec bred her to be his own horse, but had to use her on a ride when they were short one particularly busy day. She was so good that “she ended up being ridden by anyone that came along just about.”

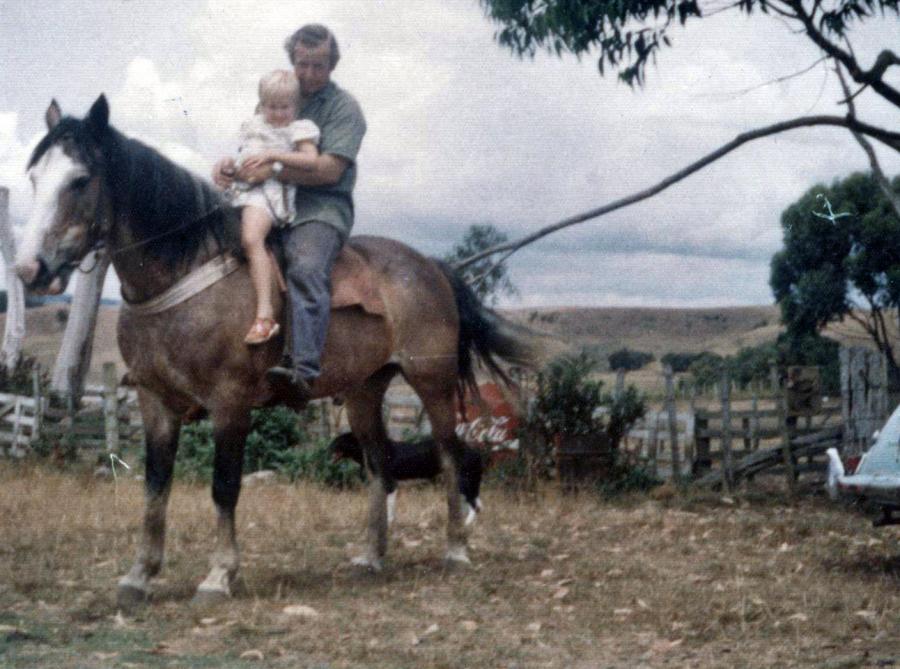

Hec taking a young child for a ride at Tasman Rides.

Hec taking a young child for a ride at Tasman Rides.

After nearly thirty years of unbelievable success, Hec sold Tasman Rides as a functional trekking business in 1997. Times were changing, and for Hec that meant moving on. Not only was 400 acres getting to be a bit much for a 64 year old to manage, but “we were sick of it. We’d been doing it too long.” Furthermore, the trekking industry had shifted. Rules were being put in place and the freedom that Hec had enjoyed was quickly diminishing. In many ways, the era during which Hec ran Tasman Rides was a golden age for the trekking world, untarnished by laws and technology.

Keeping 100 acres of the original farm, he and Clare built their dream home overlooking the Kaipara Harbour and satisfied themselves with managing a herd of 80 odd steers. It wasn’t long before another generation of Aitkenheads would be helping out at Tasman Rides, however, with Shona and her husband Dave’s eldest daughter Courtney getting a job at the newly-owned company in the early 2000s. A few more years down the track, their youngest daughter Nikki (myself), began work there. Over ten years after Hec had sold Tasman Rides, his legacy continued. On more than one occasion clients asked me if “that old guy Hec” was still around, and told me about their great experiences trekking at Tasman Rides during the ’70s and the ’80s. While he no longer has anything to do with the business, Hec is still “around,” and remembers it all like it was yesterday. Hec’s success is an inspiration to all the modest Kiwi farmers and horsemen out there like him.

Hec with his two granddaughters, Nikki (middle) and Courtney (right), on the ‘famous’ trekkers Heidi and Strawberry, about 15 years ago.

Hec with his two granddaughters, Nikki (middle) and Courtney (right), on the ‘famous’ trekkers Heidi and Strawberry, about 15 years ago.